By Faithe McCreery

My decision to pursue a career in the museum field was informed, more than anything, by a simple, yet elegant proposition: that museums have the potential to impact the social wellbeing of their visitors, and of larger society. I think that most museum professionals, and many amateur museum fans, would agree with this notion—and some of the most renowned museological scholars have elaborated on this potential, particularly in recent decades. One of my favorites is Stephen Weil, who describes the progressive museum as one that “through its public service orientation, use[s] its very special competencies in dealing with objects to contribute positively to the quality of individual human lives and to enhance the wellbeing of human communities” (2002, p. 29).

My decision to pursue a career in the museum field was informed, more than anything, by a simple, yet elegant proposition: that museums have the potential to impact the social wellbeing of their visitors, and of larger society. I think that most museum professionals, and many amateur museum fans, would agree with this notion—and some of the most renowned museological scholars have elaborated on this potential, particularly in recent decades. One of my favorites is Stephen Weil, who describes the progressive museum as one that “through its public service orientation, use[s] its very special competencies in dealing with objects to contribute positively to the quality of individual human lives and to enhance the wellbeing of human communities” (2002, p. 29).

While pursuing my master’s degree in museology, I remained fascinated by the interplay between museology and social justice—but I also found that empirical research into this topic was somewhat lacking. All of that inspirational literature is great, I thought, but how does this theory play out in practice? It was to provide some sort of answer to this question that I opted to conduct my thesis research on historical prison museums-facilities that were once operating prisons, but have since been decommissioned and opened to the public as tourist sites–and the ways that they address the social aspects of incarceration. (For my full thesis, see Interpreting Incarceration: How Historical Prison Museums are Addressing the Social Aspects of Criminal Justice, published by the University of Washington in 2015.)

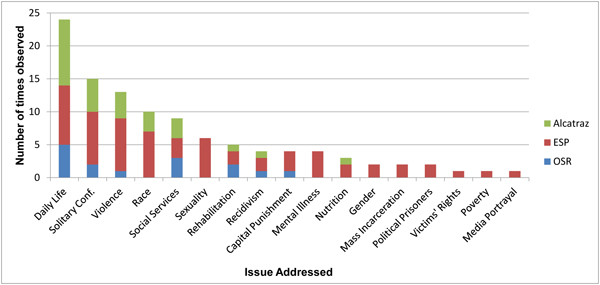

I conducted a case study analysis of three historical prison museums: Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Alcatraz Island in San Francisco, and the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio—three sites that had been identified, in the professional literature or by other museum professionals, as actively working to address social issues in their interpretation. During semi-structured group interviews with each museum’s core interpretive staff, I asked questions about their institutions’ goals and objectives, the interpretive methods that they employ, and their perceptions about the pros and cons of addressing social content. (I also performed a content analysis of the audio tour at each site, the results of which appear below.) My results were particularly encouraging.

While only one of the case institutions explicitly addresses social issues in its mission statement, the staff at all three institutions reported that they keep social aspects in mind while performing their jobs—embodying a sort of “unwritten mission” that they will seek to impact the greater social good through the topics they choose to address and the means by which they do so. Strong leadership, a culture of collaboration, and investment in community partnerships help these museums to keep their values at the forefront of their practice, and to decide when and how to address socially meaningful content.

The museum professionals that I interviewed were frank in recounting the risks of interpreting incarceration as a social issue. Tackling difficult subject matter can prove internally divisive: one interviewee reported waiting years for Board turnover to shift his museum’s political climate and pave the way for more progressive interpretation. Interpreting social content also increases museums’ vulnerability to outside criticism or reputational damage. “It’s scary. We could really mess up. We could offend someone really bad[ly],” said one individual. There are also power dynamics at play, particularly when staff members have had no personal experience with the criminal justice system. One staff member at the Ohio State Reformatory provided a particularly salient example:

We just received word that we will be receiving the actual electric chair that executed over 300 people in the state of Ohio…[The Board is] excited; we all are…but we’ve got to be prepared for that…You know, what’s our responsibility to that history of execution, without exploiting it?

Prison bunk at Ohio State Reformatory

Finally, staff at all three sites seek to strike a balance between providing socially meaningful content and meeting visitors’ expectations for a leisure time activity. “If someone comes in wanting to hear about the escape attempts and Al Capone,” said one individual, “you can’t really ambush that person and force them to have a conversation that they’re not excited to have."

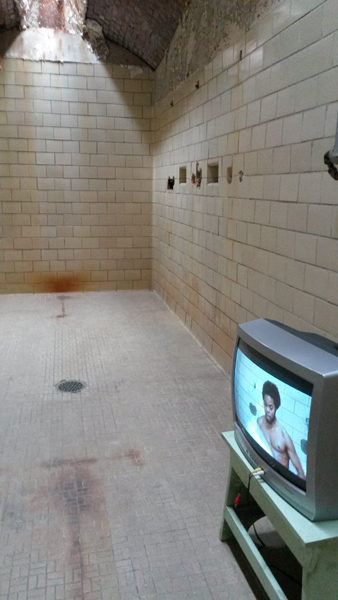

Art installation at Eastern State Penitentiary

While the risks of addressing social content are undeniable, my interview data are more than encouraging for museum professionals seeking to increase the social value of their interpretation. My interview subjects unanimously reported that interpreting social content helps to demonstrate their museums’ relevance to contemporary society—a classic struggle for history museums—and that social content is a means of stimulating dialogue and critical thinking. I was surprised to learn that all three sites had experienced increases in visitorship and revenue since beginning to interpret the social aspects of incarceration. Staff also perceived, across the board, that despite their fears, the shift toward socially meaningful content actually enhanced each museum’s reputation in the public eye. “I think that a lot of visitors have been waiting for this for a long time,” one interviewee told me. Perhaps most encouraging of all, my data show that addressing social issues affords museum staff with a greater job satisfaction and sense of meaning. “It can feel really good to be a part of that, to be a part of an institution that’s doing that,” said one interviewee. “[It helps with] everything from funding opportunities to visitor interest to having a reason to come to work in the morning...” echoed another.

Art installation by Ai Weiwei at Alcatraz

While these museum professionals surely wouldn’t have articulated it in so many words, what they showed me in those interviews was that that they perform their jobs every day with incredible bravery—and that, risks aside, their efforts are well worth it. That is the single most important thing that I will take out of my research. As a brand-new curator at a local history museum—where “local history” includes the ghastly precursors, actuality, and repercussions of the Civil War—I can’t afford not to.

Works Cited

- Weil, S. E. (2002). Making museums matter. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books.

Faithe McCreery earned a Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology from the University of Washington (Seattle) in 2012, and a Master of Arts in Museology from the University of Washington in 2015. She is currently the Curator and Public Engagement Specialist at the Jefferson County Museum in Charles Town, West Virginia.

Add new comment